Gender refers to the characteristics of women, men, girls and boys that are socially constructed. This includes norms, behaviours and roles associated with being a woman, man, girl or boy, as well as relationships with each other. As a social construct, gender varies from society to society and can change over time.

Gender is hierarchical and produces inequalities that intersect with other social and economic inequalities. Gender-based discrimination intersects with other factors of discrimination, such as ethnicity, socioeconomic status, disability, age, geographic location, gender identity and sexual orientation, among others. This is referred to as intersectionality.

Gender interacts with but is different from sex, which refers to the different biological and physiological characteristics of females, males and intersex persons, such as chromosomes, hormones and reproductive organs. Gender and sex are related to but different from gender identity. Gender identity refers to a person’s deeply felt, internal and individual experience of gender, which may or may not correspond to the person’s physiology or designated sex at birth.

Gender influences people’s experience of and access to healthcare. The way that health services are organized and provided can either limit or enable a person’s access to healthcare information, support and services, and the outcome of those encounters. Health services should be affordable, accessible and acceptable to all, and they should be provided with quality, equity and dignity.

Gender inequality and discrimination faced by women and girls puts their health and well-being at risk. Women and girls often face greater barriers than men and boys to accessing health information and services. These barriers include restrictions on mobility; lack of access to decision-making power; lower literacy rates; discriminatory attitudes of communities and healthcare providers; and lack of training and awareness amongst healthcare providers and health systems of the specific health needs and challenges of women and girls.

Consequently, women and girls face greater risks of unintended pregnancies, sexually transmitted infections including HIV, cervical cancer, malnutrition, lower vision, respiratory infections, malnutrition and elder abuse, amongst others. Women and girls also face unacceptably high levels of violence rooted in gender inequality and are at grave risk of harmful practices such as female genital mutilation, and child, early and forced marriage. WHO figures show that about 1 in 3 women worldwide have experienced either physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence or non-partner sexual violence in their lifetime.

Harmful gender norms – especially those related to rigid notions of masculinity – can also affect boys and men’s health and wellbeing negatively. For example, specific notions of masculinity may encourage boys and men to smoke, take sexual and other health risks, misuse alcohol and not seek help or health care. Such gender norms also contribute to boys and men perpetrating violence – as well as being subjected to violence themselves. They can also have grave implications for their mental health.

Rigid gender norms also negatively affect people with diverse gender identities, who often face violence, stigma and discrimination as a result, including in healthcare settings. Consequently, they are at higher risk of HIV and mental health problems, including suicide.

noun: gender; plural noun: genders

1. the male sex or the female sex, especially when considered with reference to social and cultural

differences rather than biological ones, or one of a range of other identities that do not correspond to

established ideas of male and female.

Example: “the singer has opted to keep the names and genders of her twins private”.

_members of a particular gender considered as a group. (“social interaction between the genders”)

_the fact or condition of belonging to or identifying as having a particular gender. (“video ads will

target users based only on age and gender”)

2. grammar

(in languages such as Latin, French, and German) each of the classes (typically masculine, feminine,

common, neuter) of nouns and pronouns distinguished by the different inflections which they have and

which they require in words syntactically associated with them. Grammatical gender is only very loosely

associated with distinctions of sex.

_the property (in nouns and related words) of belonging to a grammatical gender. (“determiners and

adjectives usually agree with the noun in gender and number”)

Origin of the word

late Middle English: from Old French gendre (modern genre), based on Latin genus ‘birth, family,

nation’. The earliest meanings were ‘kind, sort, genus’ and ‘type or class of noun, etc.’ (which was

also a sense of Latin genus).

The words sex and gender have a long and intertwined history. In the 15th century gender expanded from its use as a term for a grammatical subclass to join sex in referring to either of the two primary biological forms of a species, a meaning sex has had since the 14th century; phrases like “the male sex” and “the female gender” are both grounded in uses established for more than five centuries.

The distinction between sex and gender is attributed to the anthropologist Margaret Mead (Sex and Temperament in Three Primitive Societies, 1935). Sex is the biological category, whereas gender is the culturally shaped expression of sexual difference: the masculine way in which men should behave and the feminine way in which women should behave. It is emphasized by de Beauvoir that in this system woman is the Other: the kind of person whose characteristics are described by contrast with the male norm. It is a central aim of much feminist thought to uncover concealed asymmetries of power in differences of gender, and to work for a society in which the polarization of gender is abolished.

In the 20th century sex and gender each acquired new uses. Sex developed its "sexual intercourse" meaning in the early part of the century (now it's more common meaning), and a few decades later gender gained a meaning referring to the behavioral, cultural, or psychological traits typically associated with one sex, as in "gender roles." Later in the century, gender also came to have application in two closely related compound terms: gender identity refers to a person's internal sense of being male, female, some combination of male and female, or neither male nor female; gender expression refers to the physical and behavioral manifestations of one's gender identity. By the end of the century gender by itself was being used as a synonym of gender identity.

Among those who study gender and sexuality, a clear delineation between sex and gender is typically prescribed, with sex as the preferred term for biological forms, and gender limited to its meanings involving behavioral, cultural, and psychological traits. In this dichotomy, the terms male and female relate only to biological forms (sex), while the terms masculine/masculinity, feminine/femininity, woman/girl, and man/boy relate only to psychological and sociocultural traits (gender). This delineation also tends to be observed in technical and medical contexts, with the term sex referring to biological forms in such phrases as sex hormones, sex organs, and biological sex. But in nonmedical and nontechnical contexts, there is no clear delineation, and the status of the words remains complicated. Often when comparisons explicitly between male and female people are made, we see the term gender employed, with that term dominating in such collocations as gender differences, gender gap, gender equality, gender bias, and gender relations. It is likely that gender is applied in such contexts because of its psychological and sociocultural meanings, the word's duality making it dually useful. The fact remains that it is often applied in such cases against the prescribed use.

Usage of sex and gender is by no means settled. For example, while discrimination was far more often paired with sex from the 1960s through the 20th century and into the 21st, the phrase gender discrimination has been steadily increasing in use since the 1980s and is on track to become the dominant collocation. Currently both terms are sometimes employed with their intended synonymy made explicit: sex/gender discrimination, gender (sex) discrimination.

Anthropology produced some of the first influential theories using the term "gender" when it began discussing "gender roles." The background to this concept lay in post–World War I research. Margaret Mead, most notably, described non-Western societies where men performed tasks that Westerners might call "feminine" and vice versa. Mead described many variations in men's and women's tasks and sexual roles in her best-selling studies (such as Coming of Age in Samoa; 1928), opening one way for scholars to reappraise the seemingly fixed behaviors of men and women and to see stereotypes as contingent rather than determined by nature. Such a reappraisal, however, lay in the wings for much of the 1950s and 1960s.

Another source of gender theory was philosophical and literary. "One is not born, one is made a woman," the French philosopher and novelist Simone de Beauvoir wrote in her 1949 best-seller, The Second Sex. This dense and lengthy description of the "making" of womanhood discussed Marxist, Freudian, literary, and anthropological theories that, according to Beauvoir, actually determined women's behavior. In her view women, in contrast to men, acted in accordance with men's view of them and not according to their own lights. This analysis drew on phenomenological and existential philosophy that portrayed the development of the individual subject or self in relationship to an object or "other." Thus, as Beauvoir extrapolated from this theory, a man formed his subjectivity in relationship to "woman" as other or object, spinning his own identity by creating images of someone or something that was not him. Instead of building selves in a parallel way, women accepted male images of them as their identity. By this view, femininity as most women lived it was an inauthentic identity determined not inevitably, as a natural condition, but as the result of a misguided choice. This insight had wide-ranging implications for future scholarship, notably in suggesting a voluntaristic aspect to one's sexual role or nature.

A second extrapolation from existentialism in The Second Sex, however, did touch on women's biological role as reproducer. For existentialists, living an authentic life entailed escaping the world of necessity or biology and acting in the world of contingency. From this creed Beauvoir posited that women were additionally living an inauthentic life to the extent that they just did nature's bidding by having children and rearing them. They should search for freedom and authenticity through meaningful actions not connected with biological necessity. The assertion that women could escape biological destiny to forge an existence apart from the family also opened the way to gender theory. A group of translators in the Northampton, Massachusetts, area working under the aegis of H. M. Parshley made The Second Sex available to an anglophone audience in the 1950s, and in 1963 Betty Friedan's Feminine Mystique further spread Beauvoir's lines of thought to Americans.

Beauvoir's was not the only French doctrine to lay some of the groundwork for gender theory. During that same postwar period Claude Lévi-Strauss, an anthropologist, developed the theory called structuralism. According to structuralist theory, people in societies lived within frameworks of thought that constituted grids for everyday behavior. These frameworks were generally binary, consisting of oppositions such as pure and impure, raw and cooked, or masculine and feminine. Binaries operated with and against one another as relationships. One could draw from structuralism that in the case of masculine and feminine, these concepts or characteristics were mutually definitional because they shared a common border, which, once crossed, tipped feminine behavior into masculine and vice versa. Although Lévi-Strauss saw these binaries as fixed, the ground was laid once again for seeing masculinity and femininity both as interlocking and as a part of culture, even though a more fixed one, as well as a part of biology.

Lévi-Strauss developed these theories in The Elementary Structures of Kinship (1949), in which he took kinship, as the fundamental organizing category of all society, to be based on the exchange of women. The American anthropologist Gayle Rubin elaborated on Lévi-Strauss in "The Traffic in Women" (1975), an article that further developed gender theory. Citing Marxist and Freudian deficiencies in thinking about women and men, Rubin essentially underscored the hierarchical character of the relationship between men and women as an ingredient of what anthropologists and sociologists were coming to call gender: "the subordination of women can be seen as a product of the relationships by which sex and gender are organized and produced." The second point Rubin extrapolated from Lévi-Strauss was that the most important taboo in all societies was the sameness of men and women. This "imperative" of sexual difference was what made "all manifest forms of sex and gender," which were thus "a socially imposed division of the sexes." This imposed sexual difference "transform[ed] males and females into 'men' and 'women.' " By 1980 the phrase "social construction of gender" was commonplace among anthropologists, sociologists, and some psychologists. To quote a 1978 textbook: "Our theoretical position is that gender is a social construction, that a world of two 'sexes' is a result of the socially shared, taken-for-granted methods which members use to construct reality" (Suzanne Kessler, Gender: An Ethnomethodological Approach, p. vii).

Gender, race, ethnicity, and social class are the most commonly used categories in sociology. They represent the major social statuses that determine the life chances of individuals in heterogeneous societies, and together they form a hierarchy of access to property, power, and prestige.

Gender is the division of people into two categories, "men" and "women." Through interaction with caretakers, socialization in childhood, peer pressure in adolescence, and gendered work and family roles, women and men are socially constructed to be different in behavior, attitudes, and emotions. The gendered social order is based on and maintains these differences.

In sociology, the main ordering principles of social life are called institutions. Gender is a social institution as encompassing as the four main institutions of traditional sociology—family, economy, religion, and symbolic language. Like these institutions, gender structures social life, patterns social roles, and provides individuals with identities and values. And just as the institutions of family, economy, religion, and language are intertwined and affect each other reciprocally, as a social institution, gender pervades kinship and family life, work roles and organizations, the rules of most religions, and the symbolism and meanings of language and other cultural representations of human life. The outcome is a gendered social order.

The source of gendered social orders lies in the evolution of human societies and their diversity in history. The gendered division of work has shifted with changing means of producing food and other goods, which in turn modifies patterns of child care and family structures. Gendered power imbalances, which are usually based on the ability to amass and distribute material resources, change with rules about property ownership and inheritance. Men's domination of women has not been the same throughout time and place; rather, it varies with political, economic, and family structures, and is differently justified by religions and laws. As an underlying principle of how people are categorized and valued, gender is differently constructed throughout the world and has been throughout history. In societies with other major social divisions, such as race, ethnicity, religion, and social class, gender is intricately intertwined with these other statuses.

As pervasive as gender is, it is important to remember that it is constructed and maintained through daily interaction and therefore can be resisted, reformed, and even rebelled against. The social construction perspective argues that people create their social realities and identities, including their gender, through their actions with others—their families, friends, colleagues. It also argues that their actions are hemmed in by the general rules of social life, by their culture's expectations, their workplace's and occupation's norms, and their government's laws. These social restraints are amenable to change—but not easily.

Gender is deeply rooted in every aspect of social life and social organization in Western-influenced societies. The Western world is a very gendered world, consisting of only two legal categories—"men" and "women." Despite the variety of playful and serious attempts at blurring gender boundaries with androgynous dress and desegregating gender-typed jobs, third genders and gender neutrality are rare in Western societies. Those who cross gender boundaries by passing as a member of the opposite gender, or by sex-change surgery, want to be taken as a "normal" man or woman.

Although it is almost impossible to be anything but a "woman" or a "man," a "girl" or a "boy" in Western societies, this does not mean that one cannot have three, four, five, or more socially recognized genders—there are societies that have at least three. Not all societies base gender categories on male and female bodies—Native Americans, for example, have biological males whose gender status is that of women. Some African societies have females with the gender status of sons or husbands. Others use age categories as organizing principles, not gender statuses. Even in Western societies, where there are only two genders, we can think about restructuring families and workplaces so they are not as rigidly gendered as they are today.

Gender was first conceptualized as distinct from sex in order to highlight the social and cultural processes that constructed different social roles for females and males and that prescribed sex-appropriate behavior, demeanor, personality characteristics, and dress. However, sex and gender were often conflated and interchanged, to the extent that this early usage was called "sex roles" theory. More recently, gender has been conceptually separated from sex and also from sexuality.

Understanding gender practices and structures is easier if what is usually conflated as sex/gender or sex/sexuality/gender is split into three conceptually distinct categories—sex (or biology, physiology), sexuality (desire, sexual preference, sexual orientation, sexual behavior), and gender (social status, position in the social order, personal identity). Each is socially constructed but in different ways. Gender is an overarching category—a major social status that organizes almost all areas of social life. Therefore bodies and sexuality are gendered—biology and sexuality, in contrast, do not add up to gender.

Conceptually separating sex and gender makes it easier to explain how female and male bodies are socially constructed to be feminine and masculine through sports and in popular culture. In medicine, separating sex from gender helps to pinpoint how much of the differences in longevity and propensity to different illnesses is due to biology and how much to socially induced behavior, such as alcohol and drug abuse, which is higher among men than women. The outcome is a greater number of recorded illnesses but longer life expectancy for women of all races, ethnicities, and social classes when compared to men with the same social characteristics. This phenomenon is known in social epidemiology as "women get sicker, but men die quicker."

As with any other aspect of social life, gender is shaped by an individual's genetic heritage, physical body, and physiological development. Socially, however, gendering begins as soon as the sex of the fetus is identified. At birth, infants are placed in one of two sex categories, based on the appearance of the genitalia. In cases of ambiguity, since Western societies do not have a third gender for hermaphrodites as some cultures do, the genitalia are now "clarified" surgically, so that the child can be categorized as a boy or a girl. Gendering then takes place through interaction with parents and other family members, teachers, and peers ("significant others"). Through socialization and gendered personality development, the child develops a gendered identity that, in most cases, reproduces the values, attitudes, and behavior that the child's social milieu deems appropriate for a girl or a boy.

Borrowing from Freudian psychoanalytic theory, Nancy Chodorow developed an influential argument for the gendering of personalities in the two-parent, heterogendered nuclear family. Because women are the primary parents, infants bond with them. Boys have to separate from their mothers and identify with their fathers in order to establish their masculinity. They thus develop strong ego boundaries and a capacity for the independent action, objectivity, and rational thinking so valued in Western culture. Women are a threat to their independence and masculine sexuality because they remind men of their dependence on their mothers. However, men need women for the emotional sustenance and intimacy they rarely give each other. Their ambivalence toward women comes out in heterosexual love–hate relationships and in misogynistic depictions of women in popular culture and in novels, plays, and operas.

Girls continue to identify with their mothers, and so they grow up with fluid ego boundaries that make them sensitive, empathic, and emotional. It is these qualities that make them potentially good mothers and keep them open to men's emotional needs. But because the men in their lives have developed personalities that make them emotionally guarded, women want to have children to bond with. Thus, psychological gendering of children is continually reproduced.

To develop nurturing capabilities in men and to break the cycle of the reproduction of gendered personality structures would, according to this theory, take fully shared parenting. There is little data on whether the same psychic processes produce similarly gendered personalities in single-parent families, in households where both parents are the same gender, or in differently structured families in non-Western cultures.

Children are also gendered at school, in the classroom, where boys and girls are often treated differently by teachers. Boys are encouraged to develop their math abilities and science interests; girls are steered toward the humanities and social sciences. The result is that women students in the United States outnumber men students in college, but only in the liberal arts; in science programs, men still outnumber women. Men also predominate in enrollment in the elite colleges, which prepare for high-level careers in finance, the professions, and government.

This data on gender imbalance, however, when broken down by race, ethnicity, and social class, is more complex. In the United States, upper- and middle-class boys are pushed ahead of girls in school and do better on standardized tests, although girls of all social statuses get better grades than boys. African-American, Hispanic, and white working-class and poor boys do particularly badly, partly because of a peer culture that denigrates "book learning" and rewards defiance and risk taking. In the context of an unresponsive educational structure, discouraged teachers, and crowded, poorly maintained school buildings, the pedagogical needs of marginal students do not get enough attention; they are also much more likely to be treated as discipline problems.

Children's peer culture is another site of gender construction. On playgrounds, girls and boys divide up into separate groups whose borders are defended against opposite-gender intruders. Within the group, girls tend to be more cooperative and play people-based games. Boys tend to play rule-based games that are competitive. These tendencies have been observed in Western societies; anthropological data about children's socialization shows different patterns of gendering. Everywhere, children's gender socialization is closely attuned to expected adult behavior.

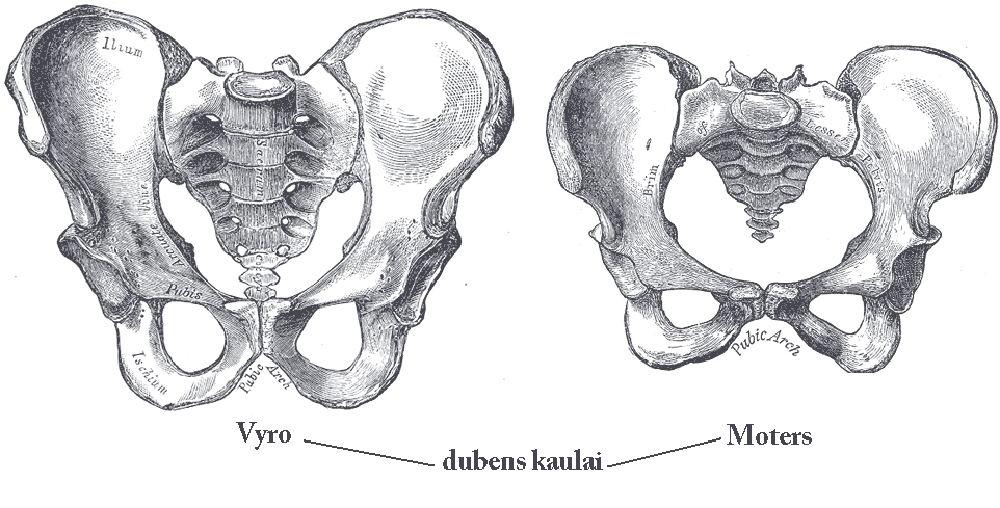

An increasing recognition of this complexity by researchers and the public has affirmed that gender sits on a spectrum: People are more and more willing to acknowledge the reality of nonbinary and transgender identities, and to support those who courageously fight for their rights in everything from all-gender bathrooms to anti-gender-discrimination laws. But underlying all of this is the perception that no matter the gender a person identifies as, they have an underlying sex they were born with. This represents a fundamental misunderstanding about the nature of biological sex. Science keeps showing us that sex also doesn’t fit in a binary, whether it be determined by genitals, chromosomes, hormones, or bones.

The perception of a hard-and-fast separation between the sexes started to disintegrate during the second wave of feminism in the 1970s and 1980s. In the decades that followed, we learned that about 1.7 percent of babies are born with intersex traits; that behavior, body shape, and size overlap significantly between the sexes, and both men and women have the same circulating hormones; and that there is nothing inherently female about the X chromosome. Biological realities are complicated. People living their lives as women can be found, even late in life, to be XXY or XY.

In the early 1900s, the U.S.-based anthropologist Aleš Hrdlička helped to found the modern study of human bones. He served as the first curator of physical anthropology at the U.S. National Museum (now the Smithsonian Institution). The skeletons Hrdlička studied were categorized as either male or female, seemingly without exception. He was not the only one who thought sex fell into two distinct categories that did not overlap. Scientists Fred P. Thieme and William J. Schull of the University of Michigan wrote about sexing a skeleton in 1957: “Sex, unlike most phenotypic features in which man varies, is not continuously variable but is expressed in a clear bimodal distribution.” Identifying the sex of a skeleton relies most heavily on the pelvis (for example, females more often have a distinctive bony groove), but it also depends on the general assumption that larger or more marked traits are male, including larger skulls and sizable rough places where muscle attaches to bone. This idea of a distinct binary system for skeletal sex pervaded—and warped—the historical records for decades.

In 1972, Kenneth Weiss, now a professor emeritus of anthropology and genetics at Pennsylvania State University, noticed that there were about 12 percent more male skeletons than females reported at archaeological sites. This seemed odd, since the proportion of men to women should have been about half and half. The reason for the bias, Weiss concluded, was an “irresistible temptation in many cases to call doubtful specimens male.” For example, a particularly tall, narrow-hipped woman might be mistakenly cataloged as a man. After Weiss published about this male bias, research practices began to change. In 1993, 21 years later, the aptly named Karen Bone, then a master’s student at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, examined a more recent dataset and found that the bias had declined: The ratio of male to female skeletons had balanced out. In part that might be because of better, more accurate ways of sexing skeletons. But also, when I went back through the papers Bone cited, I noticed there were more individuals categorized as “indeterminate” after 1972 and basically none prior.

Allowing skeletons to remain unsexed, or “indeterminate,” reflects an acceptance of the variability and overlap between the sexes. It does not necessarily mean that the skeletons classified this way are, in fact, neither male nor female, but it does mean that there is no clear or easy way to tell the difference. As science and social change in the 1970s and 1980s revealed that sex is complicated, the category of “indeterminate sex” individuals in skeletal research became more common and improved scientific accuracy.

For generations, the false perception that there are two distinct biological sexes has had many negative indirect effects. It has muddied historical archaeological records, and it has caused humiliation for athletes around the globe who are closely scrutinized. In the mid-1940s, female Olympic athletes went through a degrading process of having their genitals inspected to receive “femininity certificates.” This was replaced by chromosome testing in the late 1960s and subsequently, hormone testing. But instead of rooting out imposters, these tests just illustrated the complexity of human sex.

It might be more convenient for the U.S. federal government to have a binary system for determining legal sex; many U.S. laws and customs are built on this assumption. But just because it’s a convenient system of classification doesn’t mean it’s right. Some countries, such as Canada, and some states in the U.S., including Oregon, now allow people to declare a nonbinary gender identity on their driver’s license or other identification documents. In a world where it is apparently debatable whether anti-discrimination laws apply to sex or gender, it is a step in the wrong direction to be writing either one into law as a strictly binary phenomenon.

The famous cases of strong, athletic, and audacious female athletes who have had their careers derailed by the Olympic “gender tests” exemplify how misguided it is to classify sex or gender as binary. These women are, like all of us, part of a sex spectrum, not a sex binary. The more we as a society recognize that, the less we will humiliate and unnecessarily scrutinize people—and the less discriminatory our world will be.

France invaded Vietnam in the later nineteenth century. Its motivations were economic and strategic, though there were wider, romantic fascinations with the Pacific in the minds of many leaders. Consequences of France’s colonial administration would include the spread of plantations producing rubber, a wealthy class of colonial owners and administrators and, ultimately, fierce and successful Vietnamese anti-colonialism.

Consequences also included new visions of gender. French officials in Vietnam became quickly confused by how the Vietnamese seemed to look, and their confusion was enhanced by a sense of superiority rooted in conquest. The men, first of all, seemed effeminate. They were small-boned and slender. Their faces seemed hairless: as a French military doctor noted, “The absence of beards and the general appearance hardly permit us to distinguish the sexes.” Vietnamese soldiers, with colorful and unfamiliar uniforms, looked like “women costumed for circus pantomime.” It was easy to ridicule the vanquished in gender terms. The French were also fascinated by eunuchs in the Vietnamese royal court—officials who had been castrated so they could not trouble women in the royal family, a widespread tradition in various parts of Asia that was actually being phased out in Vietnam. Eunuchs were described as “human monsters,” with the vices of both sexes. Add to this a standard conqueror fear that Vietnamese men were dangerously oversexed—even though this did not at all comport with the idea of effeminacy—and the sense of weirdness could be overwhelming, though also easily justifying the belief that superior French people should rule.

Women were also scrutinized. First impressions by upper-class French officials emphasized how ugly Vietnamese women were—thick bodied, devoted to physical labor (as were French peasant women, but the colonial officials rarely saw them). “A man or a woman?” one French intellectual asked: “In this country, one never knows: same costume, same ugliness.” But women—again, the contradictions, held together only by the belief in superiority—were also sexually immoral libertines, easily induced into affairs with the colonialists. There was a widespread belief that many Vietnamese families indulged in incest, so few young girls could avoid molestation.

By 1900, with French administration fully established, another voice was heard: French women resident in the colonies. They viewed themselves as representing French civilization, eager to set up households that looked just like those back home (though with more local servants, of course, since they were cheap). They disliked Vietnamese women who formed relationships with French men—as an observer (male) put it, “Some of them display a ferocious jealousy in this regard.” They were eager to promote efforts to teach Vietnamese women European-style respectability and domesticity, even though this often involved more emphasis on subservience to fathers and husbands than the Vietnamese themselves had traditionally urged.

Here, then, was massive gender contact—even though this contact was a byproduct of other, expansive imperialist goals. Europeans had firm gender standards at this point, emphasizing how different men and women were. This fact, plus their status as nervous conquerors, made it easy to find another gender system strange and reprehensible, though also sometimes exciting. Weirdness and exaggeration are common features when one society encounters the gender standards of another. So, when conquest is involved, are efforts to run down local masculinity. Habits of colonial administration—from underrating the local military to assuming that local women seek sexual relationships—are powerful results of these kinds of contacts.

What about the other part of the exchange? Some Vietnamese would deeply resent French attitudes. Others might seek to adjust gender behavior, including styles of dress, to appear more respectable, and this could have frivolous, or demeaning, or liberating results, depending on the situation. Some would be eager to reassert older standards, including a sense of proud masculinity; this would factor into later anti-colonial violence, when a colonial tendency to dis- count military prowess might also make resistance easier. It was unlikely that gender standards, either for those in occupation or for those being occupied, could ever return to their pre-contact levels.

Contact possibilities have many faces. A society that stresses women’s deference may encounter one that believes women are more moral than men. A society that values masculinity but in which men are relatively short may meet another society that thinks masculinity is only truly possible when men are tall. A society tolerant of homosexuality may meet one rigorously repressive, a key issue in the world right now. The permutations are numerous, intriguing and often extremely important in defining relationships between societies and in stimulating change in gender standards when contact occurs.

All cultures of the world must deal with the division of labor between the sexes, and exactly how they do this has been the topic of much research and debate. Like culture, the awareness and recognition of sex and gender differences, and of course similarities, have played a prominent role in the development of contemporary knowledge in psychology. This recognition is complemented by an abundance of studies in cross-cultural psychology and anthropology that have been concerned with the relationship between culture and gender.

Even though biological factors may impose predispositions and restrictions on development, sociocultural factors are important determinants of development (Best & Williams, 1993; Munroe & Munroe, 1975/1994; Rogoff, Gauvain, & Ellis, 1984). Culture has profound effects on behavior, prescribing how babies are delivered, how children are socialized, how children are dressed, what is considered intelligent behavior, what tasks children are taught, and what roles adult men and women will adopt. The scope and progression of the children’s behaviors, even behaviors that are considered biologically determined, are governed by culture. Cultural universals in gender differences are often explained by similarities in socialization practices, while cultural differences are attributed to differences in socialization.

One of the best known, although often questioned, examples of cultural diversity in gender-related behaviors is Margaret Mead’s classic study of three tribes in New Guinea (Mead, 1935). Mead reported that, from a Western viewpoint, these societies created men and women who are both masculine and feminine and who reversed the usual gender roles. The pervasive nature of sex differences in behaviors was poignantly illustrated in the Israeli kibbutz, established in the 1920s, where there was a deliberate attempt to develop egalitarian societies (Rosner, 1967; Snarey & Son, 1986; Spiro, 1956). Initially, there was no sexual division of labor. Both women and men worked in the fields, drove tractors, and worked in the kitchen and in the laundry. However, as time went by and the birth rate increased, it was soon discovered that women could not undertake many of the physical tasks of which men were capable. Women soon found themselves in the same roles from which they were supposed to have been emancipated—cooking, cleaning, laundering, teaching, caring for children. The kibbutz attempts at equitable division of labor seemed to have little effect on the children. Carlsson and Barnes (1986) found no cultural or sex differences between kibbutz raised children and Swedish children regarding how they conceptualized typical female and male sex role behaviors or in their sextyped self-attributions.

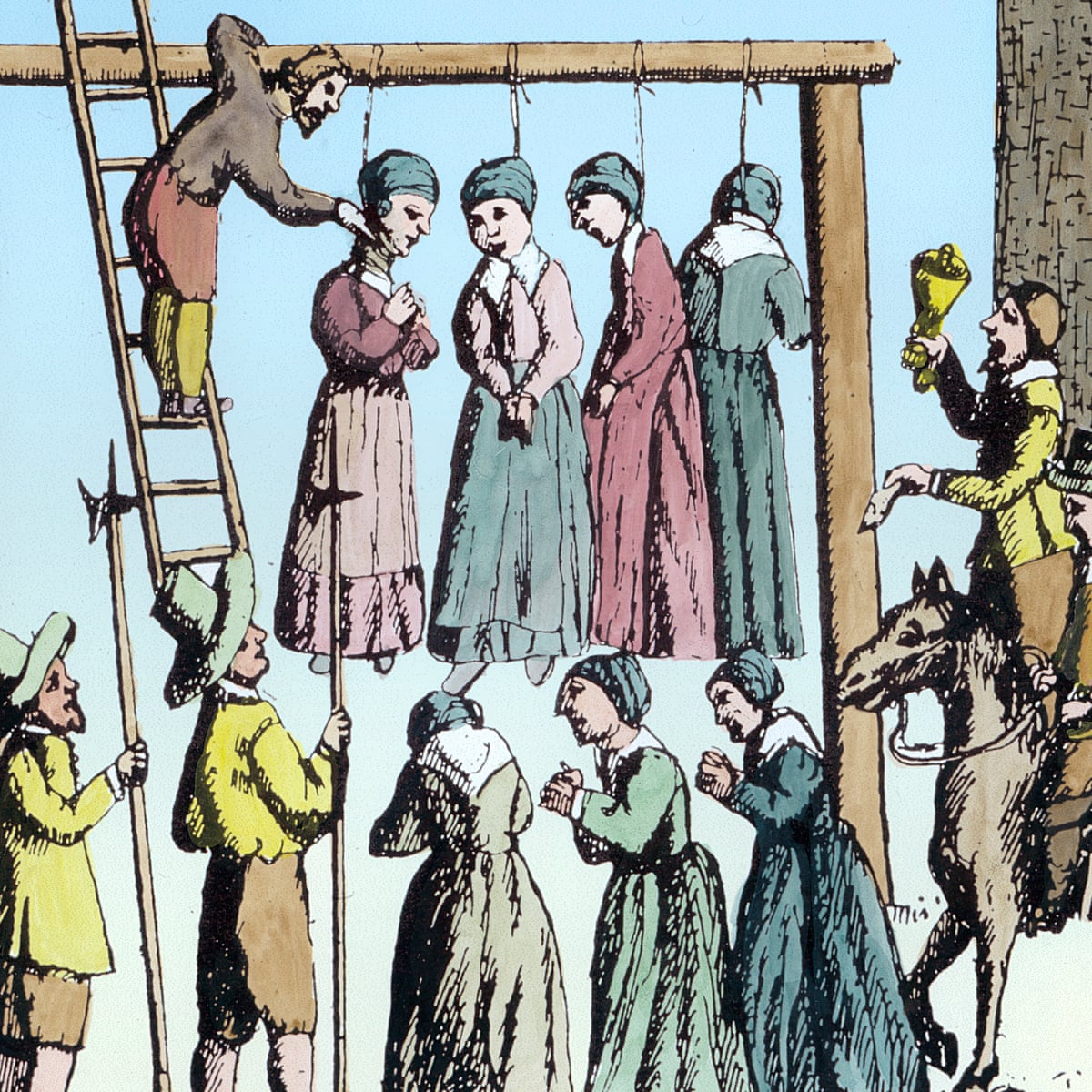

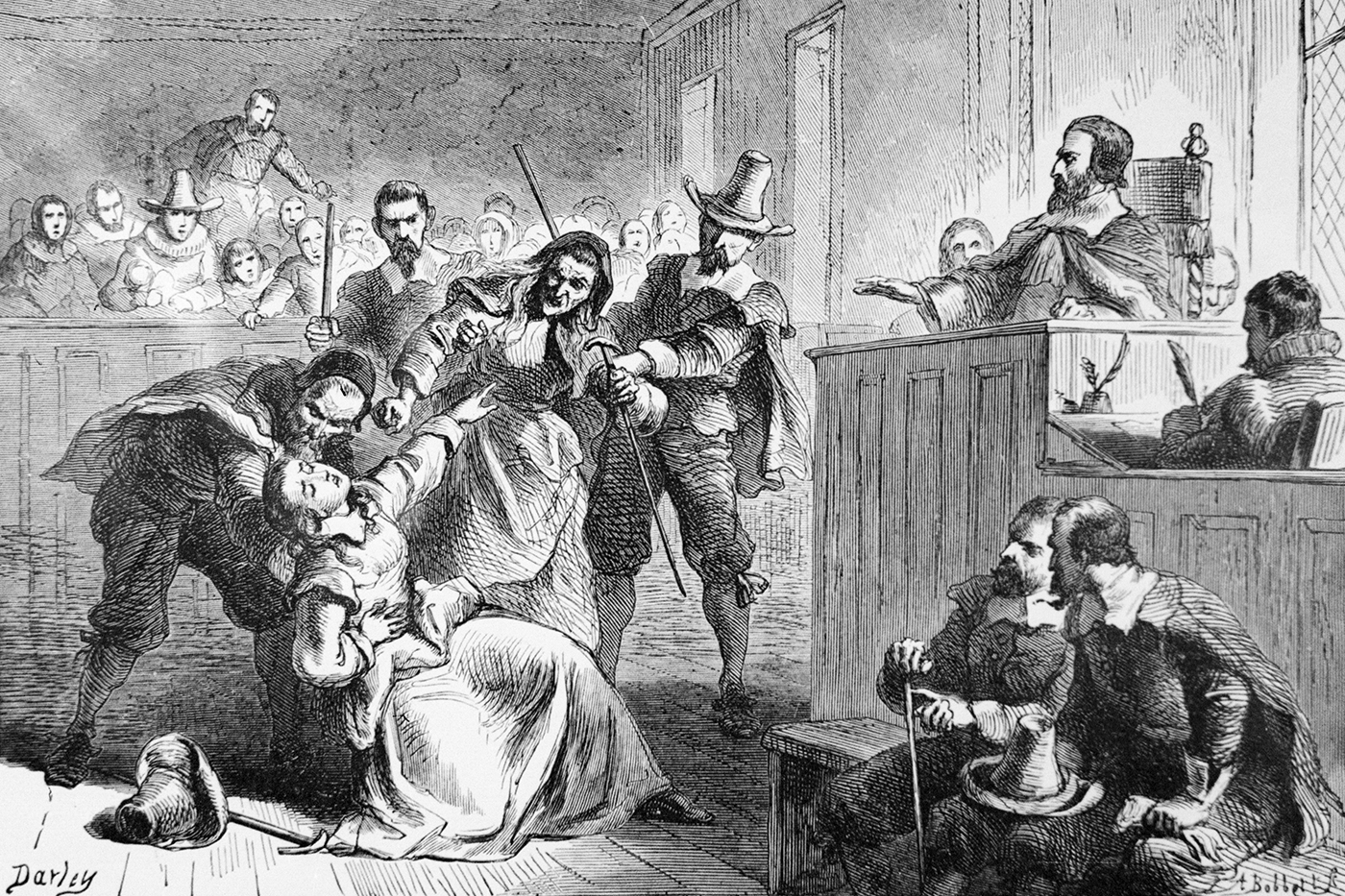

One of the most important insights in women's and then gender history began with a simple question—Did women have a Renaissance?—first posed by the historian Joan Kelly in 1977. Her answer, "No, at least not during the Renaissance," led to intensive historical and literary research as people attempted to confirm, refute, modify, or nuance her answer. This question also contributed to the broader questioning of the whole notion of historical periodization. If a particular development had little, or indeed a negative, effect on women, could it still be called a "golden age," a "Renaissance," or an "Enlightenment"? Can the seventeenth century, during which hundreds or perhaps thousands of women were burned as witches on the European continent, still be described as a period of "the spread of rational thought"?

Kelly's questioning of the term "Renaissance" has been joined more recently by a questioning of the term "early modern." Both historians and literary scholars note that there are problems with this term, as it assumes that there is something that can unambiguously be called "modernity," which is usually set against "traditional" and linked with contemporary Western society. The break between "medieval" and "early modern" is generally set at 1500, roughly the time of the voyages of Columbus and of the Protestant Reformation, but recently many historians argue that there are more continuities across this line than changes. Some have moved the decisive break earlier—to the Black Death in 1347 or even to the twelfth century—or have rejected the notion of periodization altogether. Gender historians, most prominently Judith Bennett, have been among those questioning the validity of the medieval/modern divide, challenging, in Bennett's words, "the assumption of a dramatic change in women's lives between 1300 and 1700" and asserting that historians must pay more attention to continuities along with changes.

During the fifteenth through the seventeenth centuries male and female writers in many countries of Europe wrote both learned and popular works debating the nature of women. Beginning in the sixteenth century, this debate also became one about female rulers, sparked primarily by dynastic accidents in many countries that led to women serving as advisers to child kings or ruling in their own right. The questions vigorously and at times viciously disputed directly concerned the social construction of gender: could a woman's being born into a royal family and educated to rule allow her to overcome the limitations of her sex? Should it? Or stated another way: which was (or should be) the stronger determinant of character and social role, gender or rank?

The most extreme opponents of female rule were Protestants who went into exile on the Continent during the reign of Mary Tudor (ruled 1553–1558), most prominently John Knox, who argued that female rule was unnatural, unlawful, and contrary to Scripture. Being female was a condition that could never be overcome, and subjects of female rulers needed no other justification for rebelling than their monarch's sex. Their writings were answered by defenses of female rule which argued that a woman's sex did not automatically exclude her from rule, just as a boy king's age or a handicapped king's infirmity did not exclude him. Some theorists asserted that even a married queen could rule legitimately, for she could be subject to her husband in her private life, yet monarch to him and all other men in her public life. As Constance Jordan has pointed out, defenders of female rule were thus clearly separating sex from gender and even approaching an idea of androgyny as a desirable state for the public persona of female monarchs.

Jean Bodin (1530–1596), the French jurist and political theorist, stressed what would become in the seventeenth century the most frequently cited reason to oppose female rule: that the state was like a household, and just as in a household the husband/father has authority and power over all others, so in the state a male monarch should always rule. Male monarchs used husbandly and paternal imagery to justify their assertion of power over their subjects, though criticism of monarchs was also couched in paternal language; pamphlets directed against the crown during the revolt known as the Fronde in seventeenth-century France, for example, justified their opposition by asserting that the king was not properly fulfilling his fatherly duties.

This link between royal and paternal authority could also work in the opposite direction to enhance the power of male heads of household. Just as subjects were deemed to have no or only a very limited right of rebellion against their ruler, so women and children were not to dispute the authority of the husband/father, because both kings and fathers were held to have received their authority from God; the household was not viewed as private, but as the smallest political unit and so part of the public realm.

Many analysts see the Protestant Reformation and, in England, Puritanism as further strengthening this paternal authority by granting male heads of household a much larger religious and supervisory role than they had under Catholicism. The fact that Protestant clergy were themselves generally married heads of household also meant that ideas about clerical authority reinforced notions of paternal and husbandly authority; priests were now husbands, and husbands priests. After the Reformation, the male citizens of many cities and villages increasingly added an oath to uphold the city's religion to the oaths they took to defend it and support it economically. For men, faith became a ritualized civic matter, while for women it was not. Thus both the public political community and the public religious community—which were often regarded as the same in early modern Europe—were for men only, a situation reinforced in the highly gendered language of the reformers, who extolled "brotherly love" and the religious virtues of the "common man."

Religious divisions were not the only development that enhanced the authority of many men. Rulers intent on increasing and centralizing their own authority supported legal and institutional changes that enhanced the power of men over the women and children in their own families. In France, for example, a series of laws were enacted between 1556 and 1789 that increased both paternal and state control of marriage. Young people who defied their parents were sometimes imprisoned by what were termed lettres de cachet, documents that families obtained from royal officials authorizing the imprisonment without trial of a family member who was seen as a source of dishonor. Men occasionally used lettres de cachet as a means of solving marital disputes, convincing authorities that family honor demanded the imprisonment of their wives, while in Italy and Spain a "disobedient" wife could be sent to a convent or house of refuge for repentant prostitutes. Courts generally held that a husband had the right to beat his wife in order to correct her behavior as long as this was not extreme, with a common standard being that he not draw blood, or that the diameter of the stick he used not exceed that of his thumb.

Access to political power for men as well as women was shaped by ideas about gender in early modern Europe. The dominant notion of the "true" man was that of the married head of household, so that men whose class and age would have normally conferred political power but who remained unmarried did not participate to the same level as their married brothers; in Protestant areas, this link between marriage and authority even included the clergy.

Notions of masculinity were important symbols in early modern political discussions. Both male and female rulers emphasized qualities regarded as masculine—physical bravery, stamina, wisdom, duty—whenever they chose to appear or speak in public. A concern with masculinity pervades the political writings of Machiavelli, who used "effeminate" to describe the worst kind of ruler. (Effeminate in the early modern period carried slightly different connotations than it does today, however, for strong heterosexual passion was not a sign of manliness, but could make one "effeminate," that is, dominated by as well as similar to a woman.) The English Civil War (1642–1649) presented two conflicting notions of masculinity: Royalist cavaliers in their long hair and fancy silk knee-breeches, and Puritan parliamentarians with their short hair and somber clothing. Parliamentary criticism of the court was often expressed in gendered and sexualized terminology, with frequent veiled or open references to aristocratic weakness and inability to control the passions.

The maintenance of proper power relationships between men and women served as a basis for and a symbol of the functioning of society as a whole. Women or men who stepped outside their prescribed roles in other than extraordinary circumstances, and particularly those who made a point of emphasizing that they were doing this, were seen as threatening not only relations between the sexes, but the operation of the entire social order. They were "disorderly," a word that had much stronger negative connotations in the early modern period than it does today, as well as two somewhat distinct meanings—outside of the social structure and unruly or unreasonable.

Women were outside the social order because they were not as clearly demarcated into social groups as men. Unless they were members of a religious order or guild, women had no corporate identity at a time when society was conceived of as a hierarchy of groups rather than a collection of individuals. One can see women's separation from such groups in the way that parades and processions were arranged in early modern Europe; if women were included, they came at the end as an undifferentiated group, following men who marched together on the basis of political position or occupation. Women were also more "disorderly" than men because they were unreasonable, ruled by their physical bodies rather than their rational capacities, their lower parts rather than their upper parts. This was one of the reasons they were more often suspected of witchcraft; it was also why they were thought to have nondiabolical magical powers in the realms of love and sexual attraction.

Disorder in the proper gender hierarchy was linked with other types of social upheaval and viewed as the most threatening way in which the world could be turned upside down. Carnival plays, woodcuts, and stories frequently portrayed domineering wives in pants and henpecked husbands washing diapers alongside professors in dunce caps and peasants riding princes. Men and women involved in relationships in which the women were thought to have power—an older woman who married a younger man, or a woman who scolded her husband—were often subjected to public ridicule, with bands of neighbors shouting insults and banging sticks and pans in their disapproval. Adult male journeymen refused to work for widows although this decreased their opportunities for employment. Fathers disinherited disobedient daughters more often than sons. The derivative nature of an adult woman's authority—the fact that it came from her status as wife or widow of the male household head—was emphasized by referring to her as "wife" rather than "mother" even in legal documents describing her relations with her children. Of all the ways in which society was hierarchically arranged—class, age, rank, race, occupation—gender was regarded as the most "natural" and therefore the most important to defend.

Gender theory developed in the academy during the 1970s and 1980s as a set of ideas guiding historical and other scholarship in the West. In social history it particularly thrived in the United States and Great Britain, with far fewer followers on the European continent. Essentially this theory proposed looking at masculinity and femininity as sets of mutually created characteristics shaping the lives of men and women. It replaced or challenged ideas of masculinity and femininity and of men and women as operating in history according to fixed biological determinants. In other words, removing these categories from the realm of biology, it made a history possible. For some, the idea of "gender history" was but another term for women's history, but for others gender theory transformed the ways in which they approached writing and teaching about both men and women. To some extent it may be hypothesized that the major change brought about by gender theory was that it complicated the study of men, making them as well as women gendered historical subjects.

Gayle Rubin’s article "The Traffic in Women" (1975) directed scholars to psychoanalysis, and for some, concepts drawn from psychoanalysis also contributed to gender theory, resulting in a limited number of historical applications by the 1990s. Rubin saw the Oedipal moment, as pinpointed first by Sigmund Freud, as being that moment when the societal norm of sexual difference was installed in each psyche. Her article publicized the French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, whose writings fused the insights of Lévi-Strauss with an updated Freudianism. Rubin admitted that Freud, Lévi-Strauss, and Lacan could be seen as advocates for the sexism of the psyche and society, yet she also valued them and urged scholars to value them for the descriptions they provided of sexism as a deeply ingrained psychosocial institution. As a result of Rubin's and others' investigations into psychoanalysis and its relevance to scholarship, some gender theory came to absorb this ingredient too.

Freud's publications between 1899 and 1939 touched on questions of women's sexuality and identity formation. His formulations saw a psychosexual development for women that depended on imaginings of the male phallus, and of the female genitalia as in essence lacking one. Privileging the phallus, as did the little boy, the little girl understood her "lack" and that of her mother as somehow a devaluation of femininity. This drove her to appreciate male superiority and to throw herself eagerly into the arms of a man (first her father and then her husband) as part of the development of a normative, heterosexual femininity with marriage and motherhood—not career—as goals. Boys, in contrast, feared that they might become castrated like their mothers, whose genitals they interpreted as deficient, and thus came to fear their fathers, repress their normal, infantile love for their mothers, and construct an ego and sense of morality based on identification with masculinity and accomplishment. In the case of both boys and girls, however, there were many roads to adult identity based on a number of ways of interpreting biology and the parental image. Thus, in two regards Freudianism became an important ingredient of gender theory: first, it posited an identity that, although related to biology, nonetheless depended on imaginings of biology in relationship to parental identities. Freeing male and female from a strict biological determinism, Freud furthermore saw psychosexual identity as developing relationally. That is, the cultural power of the male phallus was only important in relationship to feminine lack of the phallus or castration. This relativity of masculine and feminine psyches informed gender theory.

The theories of Jacques Lacan nuanced Freudianism and became both influential and contested in gender theory. Lacan described the nature of the split or fragmented subject in even stronger terms. Freud had seen the rational, sexual, and moral regimes within the self as in perpetual contest. In an essay on the "mirror stage" in human development, Lacan claimed a further, different splitting. The baby gained an identity by seeing the self first in terms of an other—the mother—and in a mirror, that is, again, in terms of an other. Both of these images were fragmented ones because the mother disappeared from time to time, as did the image in the mirror. The self was always this fragmented and relational identity. Lacan also posited language as a crucial influence providing the structures of identity and the medium by which that identity was spoken. In speaking, the self first articulated one's "nom" or name—which was the name of one's "father"—and simultaneously and homonymically spoke the "non," the proscriptions or rules of that language, which Lacan characterized as the laws of the "father" or the laws of the phallus. Lacanianism added to gender theory a further sense of the intertwined nature of masculinity and femininity, beginning with identity as based on the maternal imago and fragmented because of it. Second, it highlighted the utterly arbitrary, if superficially regal, power of masculinity as an extension of the phallus, or cultural version of the male organ. Third, the fantasy nature of the gendered self and indeed of all of human identity and drives received an emphasis that became crucial to some practitioners of gender history.

Under the sign of what came to be known as "French feminism," French theorists picked up on Lacanian, structuralist, and other insights to formulate a position that contributed to gender theory. For these theorists, such as Luce Irigaray, masculine universalism utterly obstructed feminine subjectivity. What Simone de Beauvoir called "the Other" had nothing to do with women but amounted to one more version of masculinity—male self-projection. Women thus appeared as erasure, as lack, and, in Irigaray's This Sex Which Is Not One (1985), as unrepresentable in ordinary terms. The woman was the divided, nonunitary, fragmented self. The result for the writing of social history were such compendia as Michelle Perrot's Une histoire des femmes est-elle possible? (Is a history of women possible?; 1984). The question of how one writes the history of fragments, "decentered subjects," and other characters for whom there are no historical conventions was addressed in some writing derived from French feminism. To some extent, Joan Scott's Only Paradoxes to Offer (1996) tried to execute that project by eliminating biography and story from her account of French feminists.

The French philosopher Michel Foucault contested the standard interpretation of social and political power as a palpable force emanating from a single source. Rather, power was almost a Nietzschean life force circulating through society, thus constituting a mesh in which all people operated. The mesh or grid of power produced subjects or, more commonly, people as they articulated its principles. Thus, for instance, in his famous History of Sexuality (1977) Foucault maintained that speaking about sex or behaving in some flauntingly sexual way was not in and of itself a liberatory act but rather an articulation of social rules about sex and thus a participation in power and the law. Foucault saw the work of the modern state as an increasingly invisible implication of people in the exercise of power around bodily issues—thus the sense in his work of biopower present in the activities of doctors, the clergy, government officials, and ordinary reformers. Downplaying or even eliminating the traditional sense of human agency, Foucault's work actually fit with some theories current in social history in the 1970s, notably that branch investigating people's behavior as opposed to their subjectivity.

Many aspects of Foucault's theories immediately fed into French social history of women. Arlette Farge, a French social and cultural historian, described the lives of eighteenth-century Parisians in a Foucauldian manner. That is, reading police and legal records, she saw those lives as "produced" and coming into being in this legal encounter (La vie fragile: Violence, pouvoirs, et solidarités à Paris au XVIIIe siècle ; 1986). In presenting answers to questioners, they gave shape to their lives, as did neighbors and other witnesses. At the same time, they protested and resisted accusations and characterizations. Farge's accounts also showed the production of gender by the law, although this theory had not yet taken on a definite shape in historical work. Similarly Foucauldian, Alain Corbin's Les filles de noce: Misère sexuelle et prostitution (1978) interpreted legalized prostitution as arising from the state's ambition to regulate and oversee even these sexual acts. Life in the brothel had its special textures, but these were sex workers' experience of the state.

Although many of these theories had more or less influence on the social history of women, in 1986 they came together when the historian Joan Scott issued a stirring manifesto about gender theory in AmericanHistorical Review. Scott's "Gender: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis" asked historians to transform social scientific understandings of gender by adding Lacanian psychoanalysis, Jacques Derrida's deconstruction (a philosophical theory showing the difficulties in assigning definite meanings or truth to texts), and Foucauldian-Nietzschean definitions of power. In her view Marxist, anthropological, and psychological moves toward understanding gender had reached a dead end because they tended to see male and female as having essential or enduring characteristics. Marxism always saw women's issues as inexorably subordinate to issues of class, and feminists who believed in Marxism had no convincing way of explaining men's oppression of women. Nor, for that matter, according to Scott, did those feminist scholars who studied patriarchy or sought out "women's voices." Despite great progress, even those who now followed the lead of the "binary oppositions" of structuralist anthropology could not account for them. The rigidity of the male-female categories in any of these systems, especially in the work of those who sought out women's "voices" and "values," kept gender from being as useful as it could be.

As palliative, Scott considered the way the trio of French theorists could overcome the rigidities of gender theory as it had evolved to the mid-1980s. Lacanian psychoanalysis rested in part on the Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure's understanding of language as a system in which words had meaning only in relationship to one another. It coupled this insight with revised Freudian ideas about the psychic acquisition of identity as a process shaped by the supremely high value placed on the phallus, and it was this value that the symbolic system of language expressed. For Scott, Lacanianism and all the psychic variation it involved were one key to understanding gender as an exigent, inescapable relationship. Foucault's theory of power as a field in which all humans operated offered another valuable insight. Scott suggested that using Foucault allowed for the introduction of gender issues into political history, thus overcoming the separation that historians had maintained between women's history and the political foundation on which most historical writing rested.

Scott also explained that gender could be a category or subject of discussion through which power operated. It could operate thus in several ways. For one, because gender meant differentiation, it could be used to distinguish the better from the worse, the more important from the less important. Using the term "feminine" articulated a lower place in a social or political hierarchy. Additionally, gender explained or assigned meaning to any number of phenomena, including work, the body, sexuality, politics, religion, cultural production, and an infinite number of other historical fields. Because many of these were fields where social history had established itself and where Scott herself had done major work as well, gender theory of her variety found a welcoming audience.

The philosopher Judith Butler offered other poststructuralist versions of gender theory that influenced historians. In two highly celebrated books, Gender Trouble (1990) and Bodies That Matter (1993), Butler argued against talking of femininity in terms of an essential womanhood. Drawing on a range of theories, Butler proposed to discuss human action less in terms of the behavior of a knowing and conscious subject and more as an iteration of social rules. The fact that actions were the iteration of rules should not lead to fatalism, Butler maintained, for such iterations in appropriate settings could have upsetting consequences and even make for social change. Bodies That Matter made an important contribution to debates in gender theory that saw gender as "constructed" and sex or the body as somehow more "real" and determined by biology. Butler's response was to deny "sex" as a ground for the "construction of gender." "Sex" was as constructed as gender, especially the construction of "sex" as being more fundamental or real than gender.

By 1990 Scott, Butler, and other scholars had provided two critiques that shaped the use of gender theory in social history. The first was the critique of universalism, meaning the critique of narratives and analyses that took women as having their womanhood in common. Although social historians had been more conscientious than most in assessing class interests, Marxist tendencies in social history tended to see class as a universal tool, one that overrode particularities such as race and gender. The critique of universals particularly brought to the fore women of color and women outside the Western framework of social history. Similarly, the critique of essentialism served to encourage more particularist studies because it denied an essence to womanhood. Denise Riley's "Am I That Name?": Feminism and the Category of "Women'' in History (1988) showed that womanhood as an essential category was constructed in the nineteenth century to represent the "social" and thus a unified essence. The critique of essentialism went even further, however. Joan Scott's "Evidence of Experience" argued that even the claiming of a group identity or essence based on one's own experience that was shared with others was impossible as an authentic or originary entity.

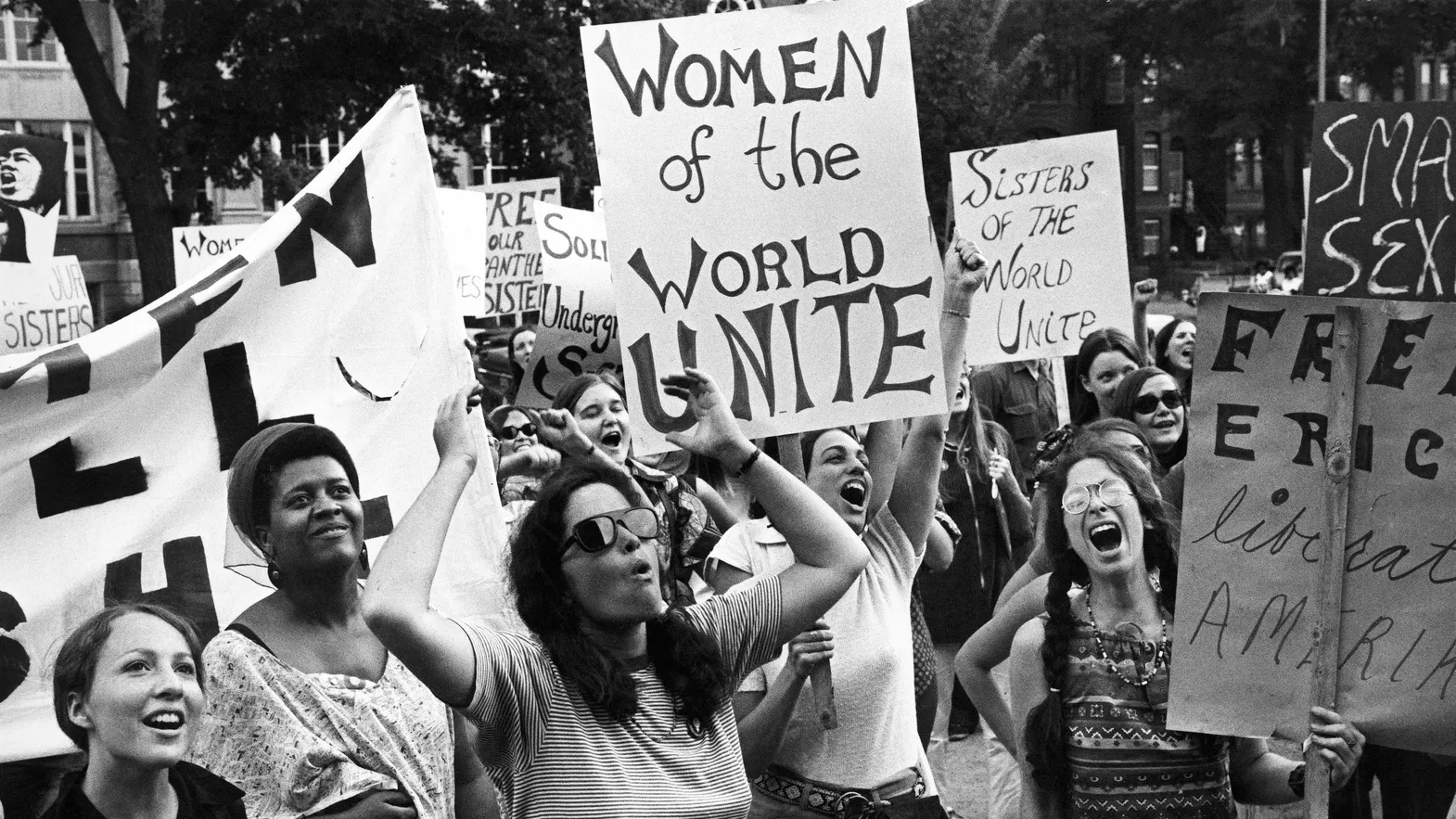

People began talking about feminism as a series of waves in 1968 when a New York Times article by Martha Weinman Lear ran under the headline “The Second Feminist Wave.” “Feminism, which one might have supposed as dead as a Polish question, is again an issue,” Lear wrote. “Proponents call it the Second Feminist Wave, the first having ebbed after the glorious victory of suffrage and disappeared, finally, into the sandbar of Togetherness.”

The wave metaphor caught on: It became a useful way of linking the women’s movement of the ’60s and ’70s to the women’s movement of the suffragettes, and to suggest that the women’s libbers weren’t a bizarre historical aberration, as their detractors sneered, but a new chapter in a grand history of women fighting together for their rights. Over time, the wave metaphor became a way to describe and distinguish between different eras and generations of feminism.

It can reduce each wave to a stereotype and suggest that there’s a sharp division between generations of feminism, when in fact there’s a fairly strong continuity between each wave — and since no wave is a monolith, the theories that are fashionable in one wave are often grounded in the work that someone was doing on the sidelines of a previous wave. And the wave metaphor can suggest that mainstream feminism is the only kind of feminism there is, when feminism is full of splinter movements.

And as waves pile upon waves in feminist discourse, it’s become unclear that the wave metaphor is useful for understanding where we are right now.

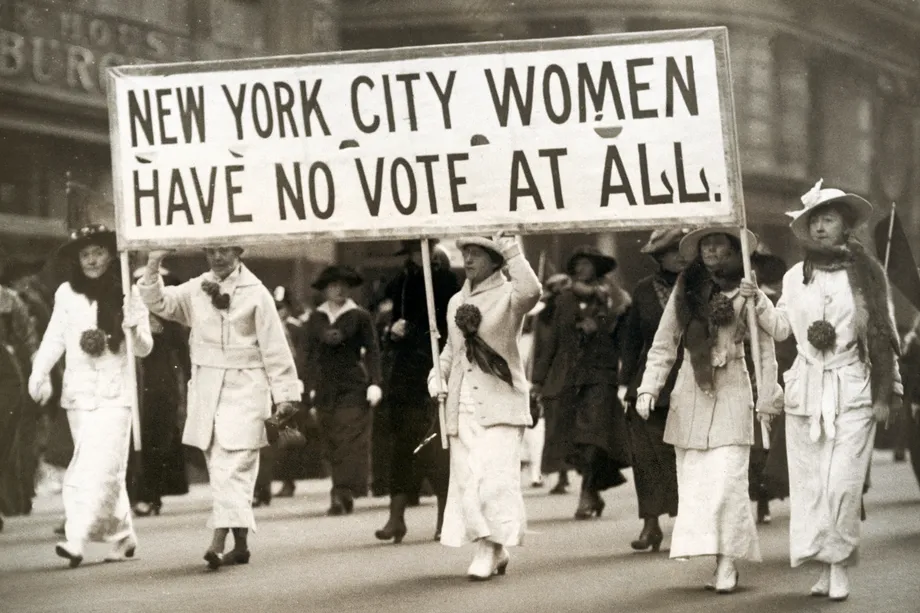

People have been suggesting things along the line of “Hmmm, are women maybe human beings?” for all of history, so first-wave feminism doesn’t refer to the first feminist thinkers in history. It refers to the West’s first sustained political movement dedicated to achieving political equality for women: the suffragettes of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

For 70 years, the first-wavers would march, lecture, and protest, and face arrest, ridicule, and violence as they fought tooth and nail for the right to vote. As Susan B. Anthony’s biographer Ida Husted Harper would put it, suffrage was the right that, once a woman had won it, “would secure to her all others.”

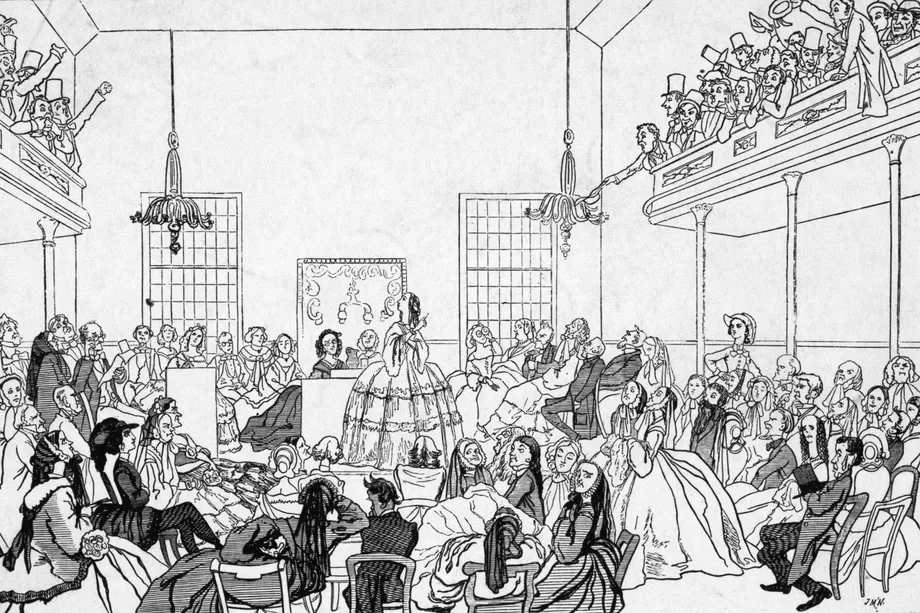

The first wave basically begins with the Seneca Falls convention of 1848. There, almost 200 women met in a church in upstate New York to discuss “the social, civil, and religious condition and rights of women.” Attendees discussed their grievances and passed a list of 12 resolutions calling for specific equal rights — including, after much debate, the right to vote.

At the time, the nascent women’s movement was firmly integrated with the abolitionist movement. Women of color like Sojourner Truth, Maria Stewart, and Frances E.W. Harper were major forces in the movement, working not just for women’s suffrage but for universal suffrage. But despite their immense work for the women’s movement, it eventually established itself as a movement specifically for white women, one that used racial animus as fuel for its work.

“If educated women are not as fit to decide who shall be the rulers of this country, as ‘field hands,’ then where’s the use of culture, or any brain at all?” demanded one white woman who wrote in to Stanton and Anthony’s newspaper, the Revolution. “One might as well have been ‘born on the plantation.’” Black women were barred from some demonstrations or forced to walk behind white women in others.

In 1920, Congress passed the 19th Amendment granting women the right to vote. In theory, it granted the right to women of all races, but in practice, it remained difficult for black women to vote.

The 19th Amendment was the grand legislative achievement of the first wave. Although individual groups continued to work — for reproductive freedom, for equality in education and employment, for voting rights for black women — the movement as a whole began to splinter. It no longer had a unified goal with strong cultural momentum behind it, and it would not find another until the second wave began to take off in the 1960s.

“One is not born but rather becomes a woman” (de Beauvoir 1953, p. 249).

The second wave of feminism begins with Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique, which came out in 1963. There were prominent feminist thinkers before Friedan who would come to be associated with the second wave — most importantly Simone de Beauvoir, whose Second Sex came out in France in 1949 and in the US in 1953 — but The Feminine Mystique was a phenomenon.

The Feminine Mystique rails against “the problem that has no name”: the systemic sexism that taught women that their place was in the home and that if they were unhappy as housewives, it was only because they were broken and perverse. “I thought there was something wrong with me because I didn’t have an orgasm waxing the kitchen floor,” (Betty Friedan).

The Feminine Mystique was not revolutionary in its thinking, as many of Friedan’s ideas were already being discussed by academics and feminist intellectuals. Instead, it was revolutionary in its reach. It made its way into the hands of housewives, who gave it to their friends, who passed it along through a whole chain of well-educated middle-class white women with beautiful homes and families. And it gave them permission to be angry.

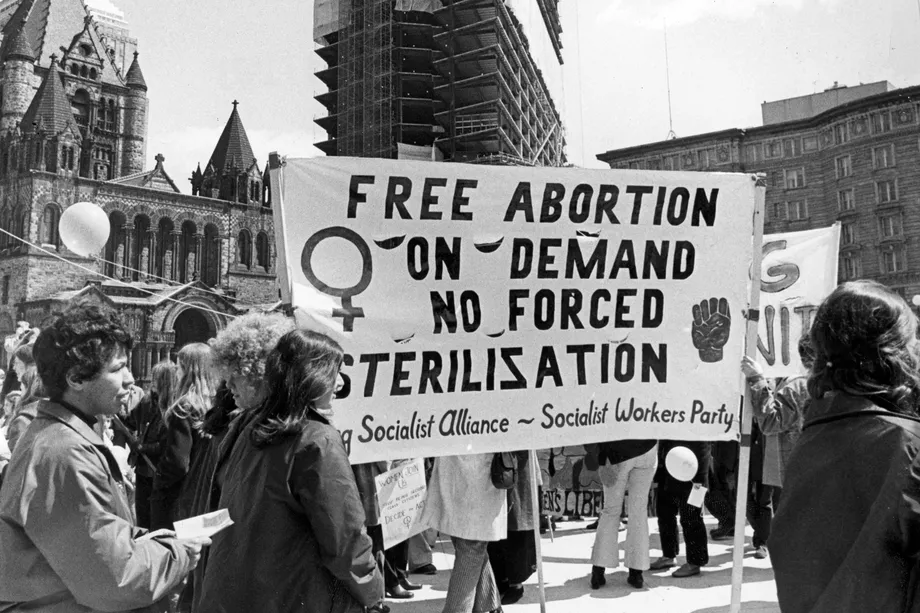

So the movement won some major legislative and legal victories: The Equal Pay Act of 1963 theoretically outlawed the gender pay gap; a series of landmark Supreme Court cases through the ’60s and ’70s gave married and unmarried women the right to use birth control; Title IX gave women the right to educational equality; and in 1973, Roe v. Wade guaranteed women reproductive freedom.

But perhaps just as central was the second wave’s focus on changing the way society thought about women. The second wave cared deeply about the casual, systemic sexism ingrained into society — the belief that women’s highest purposes were domestic and decorative, and the social standards that reinforced that belief — and in naming that sexism and ripping it apart.

The second wave cared about racism too, but it could be clumsy in working with people of color. As the women’s movement developed, it was rooted in the anti-capitalist and anti-racist civil rights movements, but black women increasingly found themselves alienated from the central platforms of the mainstream women’s movement.

“I don’t think of myself as a feminist,” a young woman told Susan Bolotin in 1982 for the New York Times Magazine. “Not for me, but for the guy next door that would mean that I’m a lesbian and I hate men.”

That image of feminists as angry and man-hating and lonely would become canonical as the second wave began to lose its momentum, and it continues to haunt the way we talk about feminism today. It would also become foundational to the way the third wave would position itself as it emerged.

It is almost impossible to talk with any clarity about the third wave because few people agree on exactly what the third wave is, when it started, or if it’s still going on. “The confusion surrounding what constitutes third wave feminism, is in some respects its defining feature.” (feminist scholar Elizabeth Evans.) But generally, the beginning of the third wave is pegged to two things: the Anita Hill case in 1991, and the emergence of the riot grrrl groups in the music scene of the early 1990s.

Early third-wave activism tended to involve fighting against workplace sexual harassment and working to increase the number of women in positions of power. Intellectually, it was rooted in the work of theorists of the ’80s: Kimberlé Crenshaw, a scholar of gender and critical race theory who coined the term intersectionality to describe the ways in which different forms of oppression intersect; and Judith Butler, who argued that gender and sex are separate and that gender is performative. Crenshaw and Butler’s combined influence would become foundational to the third wave’s embrace of the fight for trans rights as a fundamental part of intersectional feminism.

Aesthetically, the third wave is deeply influenced by the rise of the riot grrrls, the girl groups who stomped their Doc Martens onto the music scene in the 1990s.

“BECAUSE doing/reading/seeing/hearing cool things that validate and challenge us can help us gain the strength and sense of community that we need in order to figure out how bullshit like racism, able-bodieism, ageism, speciesism, classism, thinism, sexism, anti-semitism and heterosexism figures in our own lives,” wrote Bikini Kill lead singer Kathleen Hanna in the Riot Grrrl Manifesto in 1991. “BECAUSE we are angry at a society that tells us Girl = Dumb, Girl = Bad, Girl = Weak.”

The word girl here points to one of the major differences between second- and third-wave feminism. Second-wavers fought to be called women rather than girls: They weren’t children, they were fully grown adults, and they demanded to be treated with according dignity. There should be no more college girls or coeds: only college women, learning alongside college men.

In part, the third-wave embrace of girliness was a response to the anti-feminist backlash of the 1980s, the one that said the second-wavers were shrill, hairy, and unfeminine and that no man would ever want them. And in part, it was born out of a belief that the rejection of girliness was in itself misogynistic: girliness, third-wavers argued, was not inherently less valuable than masculinity or androgyny.

Third-wave feminism had an entirely different way of talking and thinking than the second wave did — but it also lacked the strong cultural momentum that was behind the grand achievements of the second wave.

The third wave was a diffuse movement without a central goal, and as such, there’s no single piece of legislation or major social change that belongs to the third wave the way the 19th Amendment belongs to the first wave or Roe v. Wade belongs to the second.

Feminists have been anticipating the arrival of a fourth wave. Internet trolls actually tried to launch their own fourth wave in 2014, planning to create a “pro-sexualization, pro-skinny, anti-fat” feminist movement that the third wave would revile, ultimately miring the entire feminist community in bloody civil war. (It didn’t work out.) But over the past few years, as #MeToo and Time’s Up pick up momentum, the Women’s March floods Washington with pussy hats every year, and a record number of women prepare to run for office, it’s beginning to seem that the long-heralded fourth wave might actually be here.

While a lot of media coverage of #MeToo describes it as a movement dominated by third-wave feminism, it actually seems to be centered in a movement that lacks the characteristic diffusion of the third wave. It feels different.

“Maybe the fourth wave is online,” said feminist Jessica Valenti in 2009, and that’s come to be one of the major ideas of fourth-wave feminism. Online is where activists meet and plan their activism, and it’s where feminist discourse and debate takes place. Sometimes fourth-wave activism can even take place on the internet (the “#MeToo” tweets), and sometimes it takes place on the streets (the Women’s March), but it’s conceived and propagated online.

Like all of feminism, the fourth wave is not a monolith. It means different things to different people. The fourth-wave feminism is queer, sex-positive, trans-inclusive, body-positive, and digitally driven. And now the fourth wave has begun to hold our culture’s most powerful men accountable for their behavior. It has begun a radical critique of the systems of power that allow predators to target women with impunity.

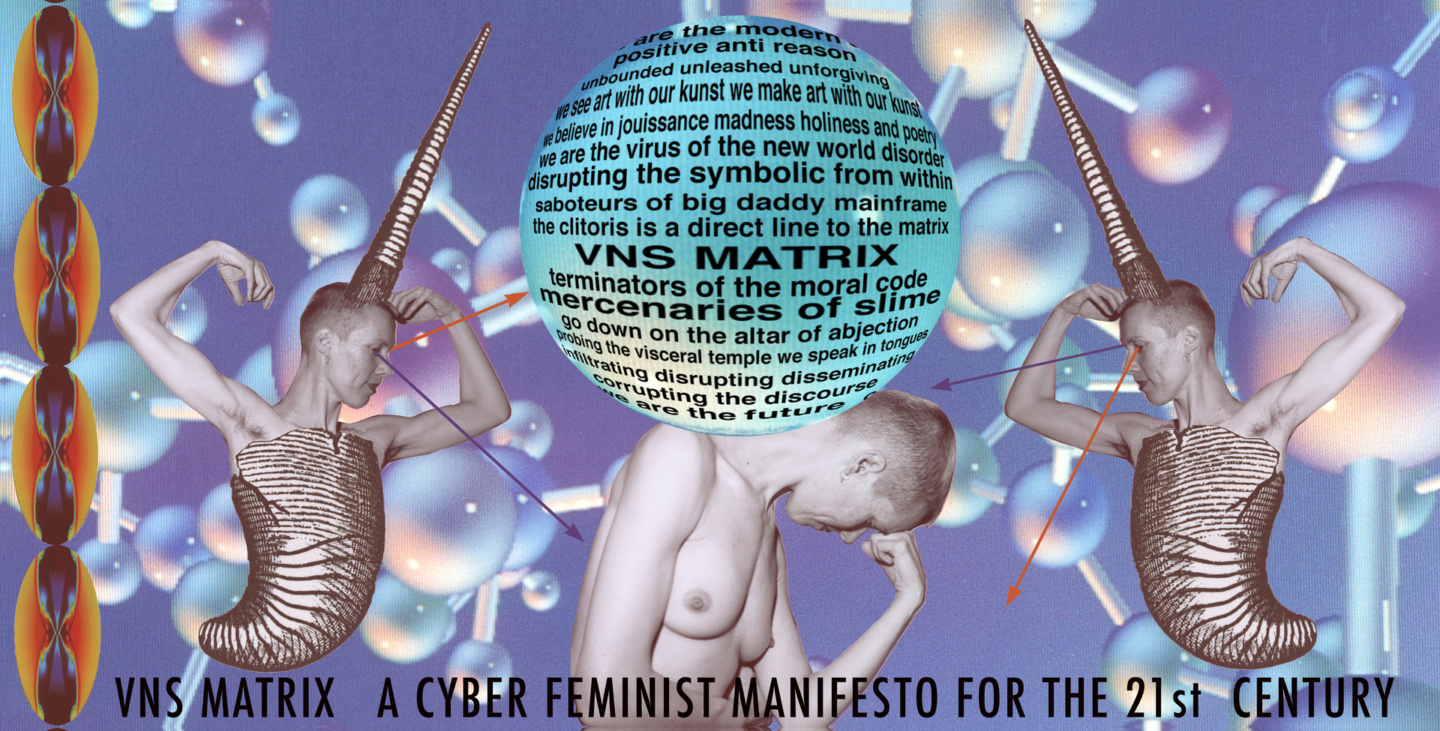

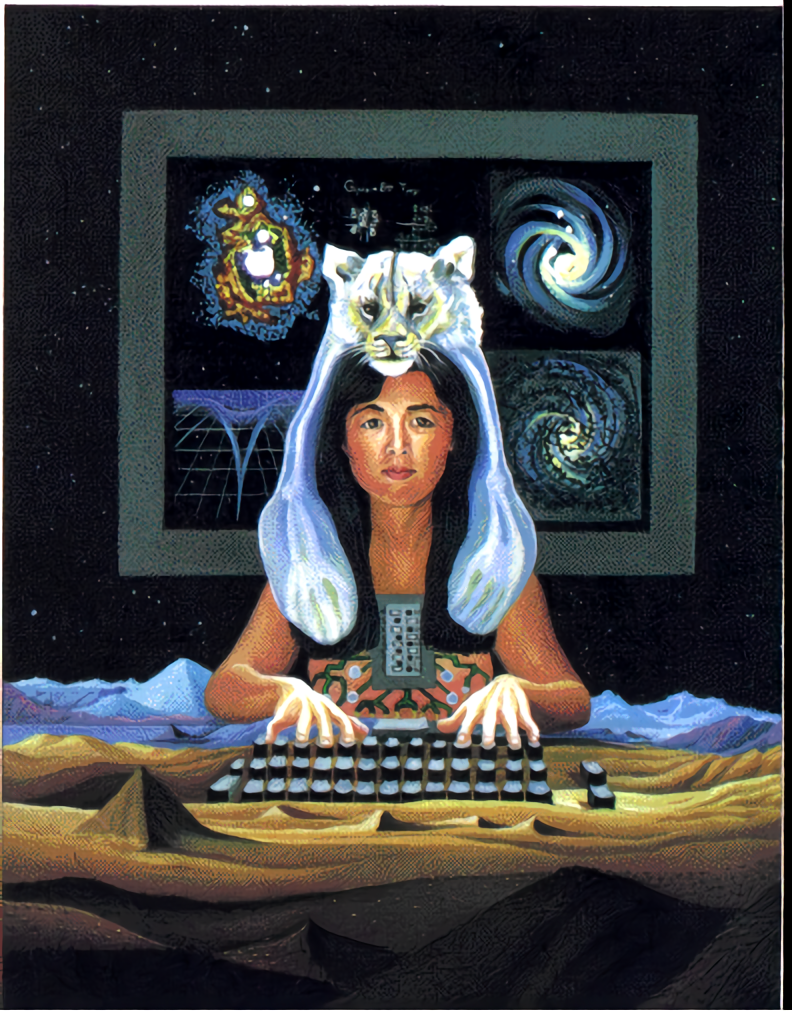

“By the late 20th century, our time, a mythic time, we are all chimeras, theorized and fabricated hybrids of machine and organism. In short, we are all cyborgs.” (post-humanist scholar and feminist theorist Donna Haraway in her iconic 1983 A Cyborg Manifesto.)

Her essay addressed the artifice around gender norms, imagined the future of feminism, and proposed the cyborg as the leader of a new world order. Part human and part machine, the cyborg challenged racial and patriarchal biases. “This,” Haraway wrote, “is the self [that] feminists must code.”

The field of cyberfeminism emerged in the early 1990s after the arrival of the world wide web, which went live in August 1991. Its roots, however, go back to the earlier practices of feminist artists like Lynn Hershman Leeson. Cyberfeminism came to describe an international, unofficial group of female thinkers, coders, and media artists who began linking up online. In the 1980s, computer technology was largely seen as the domain of men—a tool made by men, for men. Cyberfeminists asked: Could we use technology to hack the codes of patriarchy? Could we escape gender online?

Haraway’s cyborg became the cyberfeminists’ ideal citizen for a post-patriarchal world, but there were other writers leaving an impression on the nascent movement, such as African-American sci-fi writer Octavia Butler. Her Xenogenesis trilogy (1987–89) is set in a post-apocalyptic future ruled by gene-trading aliens. Butler’s books broke with conservative conceptions of race and biology, describing aliens that were neither male nor female but a third sex, and who practiced interspecies breeding.

Cyberfeminism’s star rose throughout the 1990s, as a growing constellation of women began to practice under its umbrella in different corners of the world, including North America, Australia, Germany, and the U.K. The VNS Matrix, a four-woman collective of “power hackers and machine lovers” in South Australia, began to identify as cyberfeminists in 1992. In their own words, the collective “decided to have some fun with French feminist theory,” coding games and inventing avatars as a way to critique the macho landscape of the early web. As one of its members, Virginia Barratt, recalled in an interview with Vice’s Motherboard, “We emerged from the cyberswamp… on a mission to hijack the toys from techno-cowboys and remap cyberculture with a feminist bent.” They wrote their own Cyberfeminist Manifesto for the 21st Century (1991) in homage to Haraway, presented as an 18-foot-long billboard, which was exhibited at various galleries across Australia. The text bulges from a 3D sphere, surrounded by images of DNA material and dancing, photomontaged women that have been transformed into scaled hybrids. “We make art with our cunts,” the manifesto reads. “We are the virus of the new world disorder.”